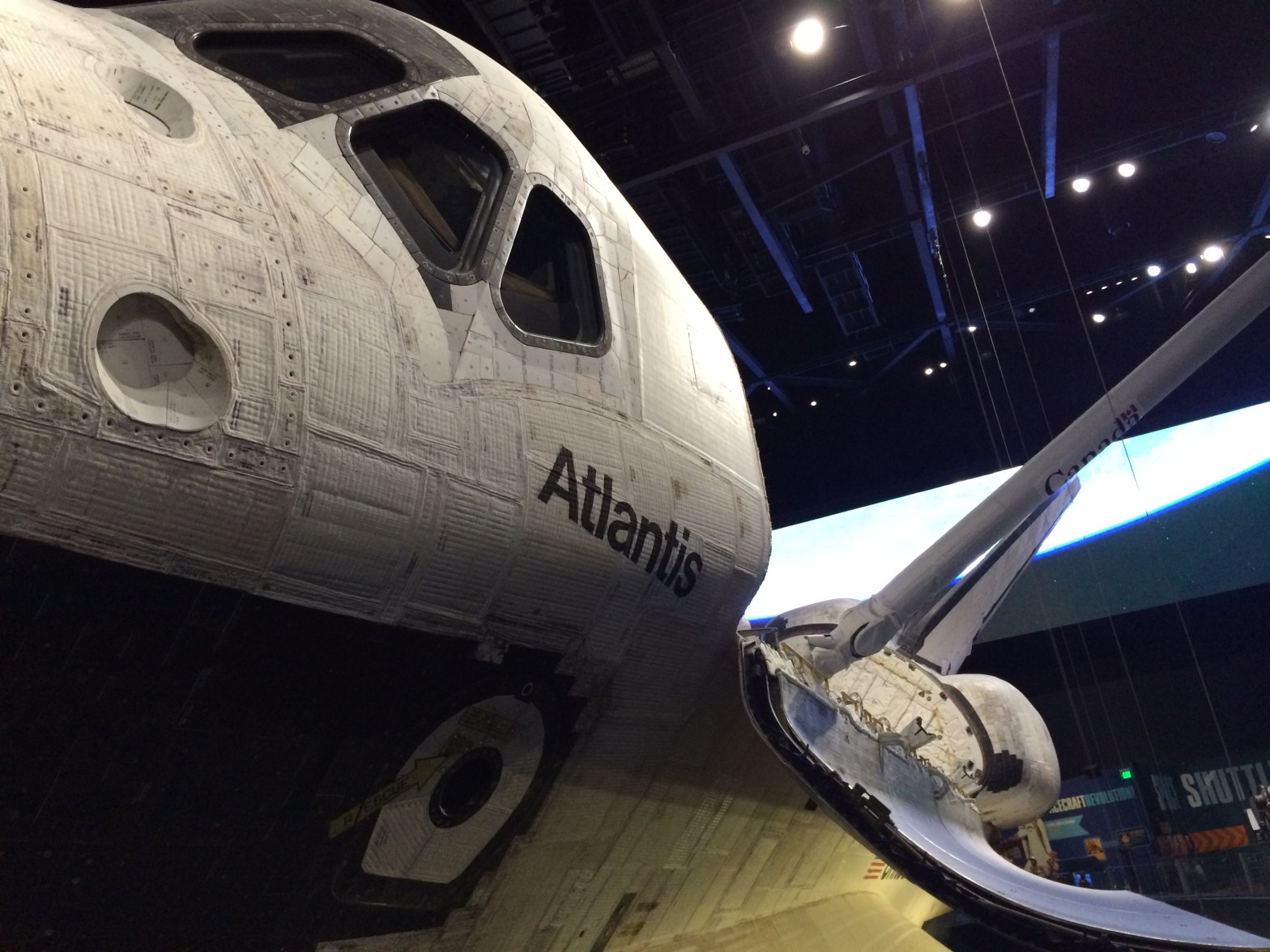

I’ve been a Star Trek fan and a space exploration enthusiast ever since I was a kid. My career as an aerospace engineer is in large measure attributable to these passions, which were refracted kaleidoscopically through each other until it was practically impossible to tease them apart. In the mind of my twelve-year-old self, spending hours drawing ill-informed but ambitious interplanetary and interstellar spacecraft, we would soon be marching briskly along a smooth, linear progression, from Mars to the outer planets and thence to the stars.

And I was going to be at the heart of it.

I wanted to be Scotty. I wanted to be Zefram Cochrane, inventor of warp drive. And I got very excited about fusion research and the prospects of a fusion propulsion system, scouring the library for books on the subject and clipping newspaper articles about each research breakthrough.

Ultimately I decided that warp drive was perhaps a bridge too far for my lifetime, but maybe those incredible sublight impulse engines could still be within our – within my – grasp. The technology seemed to be simultaneously a worthy and an attainable goal. After all, fusion = impulse engine, right?

So, for this post I thought it would be fun to take a look at exactly how amazing even the most mundane propulsion in Star Trek actually is, and to take stock of exactly how advanced such technology would be in comparison to what we have or can even imagine today.

Of course, Star Trek is notoriously inconsistent in its propulsion capabilities. For instance, there’s an alleged warp drive scale for The Original Series, where each warp factor is the cube root of a multiple of the speed of light c, i.e. Warp 1 = 1c, Warp 2 = 8c, Warp 3 = 27c, and so on. At Warp 3, it would take about 7 months to travel 16 light years and visit the Vulcans at 40 Eridani A. Unfortunately that scale doesn’t actually make sense in the context of the show itself, where such speeds are much too slow to be consistent with what we see on-screen of the Enterprise’s 5-year mission.

A re-calibrated warp scale would be associated with Star Trek: The Next Generation and its sequel series, although on-screen references would remain grossly inconsistent. A United Federation of Planets that is 1000 light-years across would still take 1 year to fly across at USS Voyager’s Warp 9.975 (not to mention the 75 years required for them to get home from the Delta Quadrant)…unless they were going merely Warp 9, which might be 1,718c and therefore more than 70% faster…or unless they were going Warp 9.9, which might be 21,473c and many times faster still. Of course, back when the NX-01 Enterprise was first getting underway at Warp 5, Warp 4.5 was somehow both 83 times the speed of light and 8,218 times the speed of light in a single episode (and per the cube-root scale, it should have been about 91 times the speed of light).

The performance of impulse drive is, I think, much less scrutinized than warp drive, but likely no more internally consistent. We do know for certain that impulse power is slower than light. So, okay, can we figure out at least some representative performance for impulse engines as depicted in Star Trek? Well, if we’re willing to accept a single data point as “representative” and not try to somehow reconcile every single reference to impulse performance across hundreds of hours of television, then yes, we can.

As it happens, one of the most explicit references for impulse power is given in Star Trek: The Motion Picture, when it was stated on screen that it took them 1.8 hours to travel from Earth to Jupiter. We can imagine that impulse acceleration is constant and powerful enough that they’re not travelling ballistically, so we can estimate their acceleration just by looking at the distance between Earth and Jupiter – which varies, but a reasonable first estimate might speculate that they traveled 500,000,000 miles. To cover that distance in 1.8 hours, Enterprise must have an average speed of ~278,000,000 miles per hour. If we assume the Enterprise is accelerating linearly and we stick to Newtonian physics (which is wrong here, but more on that later), that would mean that after 1.8 hours they’re now going about 86% the speed of light. They’ve been accelerating at about 40,000 m/s2, which is to say over 4000 G’s. For comparison, the Saturn V rocket that sent people to the moon had a maximum acceleration of around 3.5 G’s, and fighter pilots might pull as many as 9 G’s.

Now we see clearly what Star Trek’s “inertial dampers” are for; they’re protecting the crew from being instantaneously liquified under such extraordinary acceleration. And thus we have our first indications that, technologically speaking, humans in 2023 are nowhere remotely close to impulse power. (This simple computation also neglects other problems associated with the Enterprise accelerating to such a high fraction of the speed of light; more to come.)

Things can be even worse. If the Enterprise wasn’t accelerating continuously the entire time, then the implication is that they rapidly accelerated to full impulse velocity and then maintained that velocity for most of the journey. If they accelerated to full impulse instantaneously and completed the journey in 1.8 hours, that would imply that full impulse is about 40% the speed of light. If full impulse is only 25% the speed of light then what was stated on screen in ST:TMP simply can’t be true. If full impulse is 50% the speed of light, then maybe what they did, roughly, is accelerate linearly for 0.3 hours and then continue at full impulse for the remaining 1.5 hours. If they did that, then while accelerating they would have covered about 50,000,000 miles, and then another 500,000,000 miles during the next 1.5 hours, putting Jupiter at that time a little nearer to its maximum distance from Earth. Accelerating to 50% of the speed of light in 0.3 hours would have meant they accelerated at about 14,000 G’s rather than 4,000 G’s.

Beyond the problem of achieving and surviving such phenomenally high accelerations, we also need to reckon with the fact that we are talking about accelerating to substantial fractions of the speed of light. In short, Newtonian physics will no longer describe the universe accurately; we need Einstein.

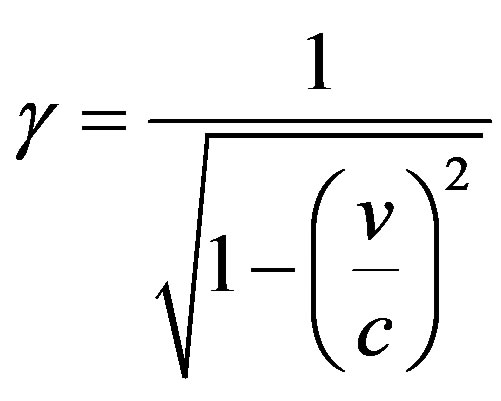

We’ll start by thinking about the time dilation factor that the crew would experience. We can compute it using our velocity as a fraction of the speed of light c, like so:

At a mere 10% of the speed of light, the time dilation factor is about one-half of one percent. Basically negligible, and so at such a (relatively) low velocity, Newtonian physics still work well. At 0.3c however, the time dilation factor is closer to 5% – still low, but no longer negligible. (For example, 5% of a year is about 18 days.). Up at a whopping 0.86c though, the time dilation factor is nearly two. You’re going to start to notice that pretty quickly.

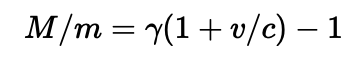

We have a further problem as well. Now that we have that time dilation factor, we can use it to calculate the ratio of propellant mass to payload – that is, how much mass is propellant used by the impulse engines, and how much is lovely, fun USS Enterprise things like the bridge and engineering and sickbay and the bowling alley that is tucked away somewhere under the hangar deck.

To be specific, if the Enterprise were to accelerate to 0.5c on impulse power, the relativistic rocket equation tells us that a whopping 42% of the mass of the Enterprise had to be expended as propellant. If the Enterprise accelerated to 0.86c, then over 72% of its mass was expended as propellant. This seems quite unlikely, considering how often the Enterprise maneuvers on impulse power, seemingly speeding up and slowing down at will.

As a result, we must conclude that even impulse drive doesn’t function purely on reaction mass; there must be some other complementary, relativistic technology in play, for instance to reduce the perceived mass of the Enterprise (maybe this is where the inertial dampers come in again). Although, if that technology is reducing the perceived mass of the propellant as well, then we’re stuck with the same unfavorable ratio, so really we would need to make the apparent mass of the Enterprise vastly less while keeping the apparent mass of the propellant the same (or vastly more!). A complicated trick.

So, fusion = impulse engine? Alas, no, not Star Trek’s miraculous impulse engine.

On the bright side, presumably we could use that same relativistic technology to also mitigate the time dilation effects of travel at sizeable fractions of light speed. It’s an interesting hypothesis, that we might develop some sort of space-time warping technology and actually use it just to travel at close to the speed of light, rather than to go faster than light (at least, at first – though this is definitely not how the discovery of warp drive is portrayed in Star Trek).

If we’re willing to settle for a lower fraction of light speed, though, things can get a little better. At 0.3c not only is the time dilation factor a seemingly-workable 5%, but also we “only” had to expend 26.6% of the Enterprise’s mass as propellant in order to accelerate. It’s still far too much to reconcile with the on-screen evidence, but the most “realistic” impulse engine we can imagine probably does max out at 0.3c or less. If we say that Jupiter and Earth were at their closest approach in ST:TMP, a distance of 365,000,000 miles, then the Enterprise had to go “only” about 200,000,000 miles per hour, which actually works out to right at 0.3c, so perhaps this is what the filmmakers intended.

So, that’s impulse drive sorta-kinda as portrayed in Star Trek: The Motion Picture. What if we were willing to go slower? Is any version of this technology even vaguely within our reach? Well, let’s cap ourselves at 10% of the speed of light and see what happens.

At 0.1c, we already saw that the time dilation factor is negligible – not even 2 hours out of every year. And that means that the propellant required to accelerate to 0.1c is just under 10% of the total mass of the ship. We can’t exactly call it the USS Enterprise anymore – at least, not Star Trek’s USS Enterprise – but it might actually be something we could eventually build.

And hey, we might even manage to go faster, at least for space missions more as we’re accustomed to them – that is, as one-way space probes or one-off round-trip expeditions, rather than a Starfleet of ships that can go anywhere and everywhere on a whim. Even up at 0.86c we’re talking about ratios of propellant to useful stuff that we’re already well-acquainted with in our history of chemical rocketry; the Saturn V rocket sitting on the launch pad was 85% propellant.

The real issue is just that the mass of the super-advanced propulsion technology in question (and to generate the power to operate it) seems likely itself to be absolutely colossal. A 0.86c spacecraft of 1,000 metric tons (lighter than many World War Two submarines and more than twice the mass of the International Space Station) would have to expend over 2,600 metric tons of propellant to accelerate to that velocity, to say nothing of slowing down.

At least a 0.1c spacecraft of the same size could accelerate to its final velocity using only 105 metric tons of propellant or so. It’s nice to catch a break wherever you can.

Baby steps, as they say.

Are you sure you don’t mean cube and not cube root? 8 would be the cube of 2, 27 would be the cube of 3, and 64 would be the cube of 4. The cube roots would be the opposite direction.

LikeLike

The warp factors themselves are the cube root of the speed (as multiples of c) that they signify.

LikeLike